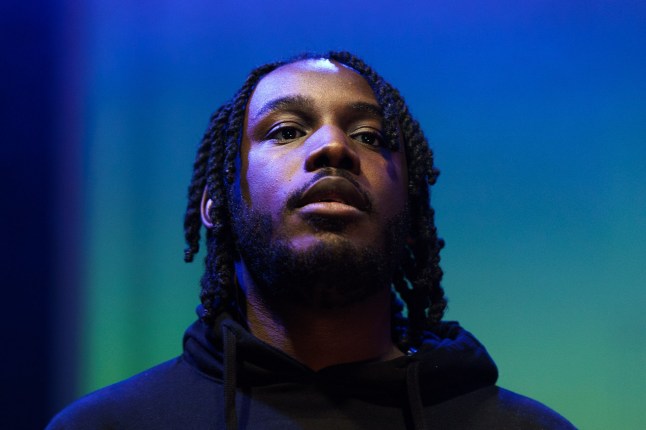

Striding into the Metro office, Kenneth Erhahon, better known as Shocka, has a contagious smile on his face. Some might feel it’s at odds with what he is here to discuss — being sectioned four times — but the 37-year-old became a mental health advocate to demonstrate that it’s possible to still live a joyful life.

From 2008, Shocka was in the rap group Marvell, which he formed with Vertex and Double S. They were a successful trio, becoming the support act for Chip, Skepta and Diversity on sell-out tours, while an average day saw them bump into stars like Rihanna and Drake at the studio.

Things were going perfectly until Marvell’s first single came out; it didn’t meet expectations, and the group was dropped by their label in 2011.

The brutal nature of the industry caused Shocka to spiral. ‘I lost my sense of reality. It was like I was playing an arcade driving game, in that I was controlling the car, but I wasn’t in it. It was the scariest feeling in the world,’ he tells Metro. He wasn’t sleeping, stopped caring about his appearance (‘I wore the same green jacket and G-SHOCK watch every day’), and was either speaking nonsensical thoughts or going completely silent.

One day in 2012, Shocka was screaming at home and was told by his family to calm down. ‘No one could snap me out of it,’ he remembers. His uncle, a doctor, recognised he was having a psychotic episode, so he called the emergency services.

Living with stigma

Shocka was sectioned, which he says is the right decision, but adds it was a frightening experience. ‘I was taken from the ambulance to a detention room and left alone overnight. I didn’t know where I was. I thought, “This is it, I’m dead”,’ he recalls.

‘After three days, I started coming back to myself, and assumed I was okay to go home, but the nurses wouldn’t allow it.’ Shocka says a ‘little scuffle’ ensued before he passed out after being injected. ‘I woke up in an unrecognisable space that they dragged or carried me into. It had a little flap on the door, and my mom was looking through it. I can still remember the concerned face.’ Shocka was diagnosed with manic depression, but has since been given a paranoid schizophrenia diagnosis.

Talking about how he passed the time during his four sectionings, which each lasted up to two and a half weeks, he explains: ‘I was left to my own devices so I would walk up and down the corridor.’

As well as the boredom, Shocka recalls the ‘eerie smell’. ‘It’s how you’d imagine the old haunted movies that play on BBC One would smell. I was speaking at a school the other day, and it had the same scent, which triggered me. Luckily, I was in the staff room, so I had space to compose myself.’

The stories behind the headlines

Hi, I’m Claie Wilson, Metro’s deputy editor.

At Metro, we’re committed to taking readers beyond the headlines with fresh perspectives on the biggest stories of the day. You can read more in-depth features like this one with our News Updates newsletter.

With expert analysis and first-hand accounts of the moments and issues shaping our world, our features inspire, educate and give you the bigger picture.

Sign up now to get the top headlines – and the stories behind them – delivered straight to your inbox every day.

Despite the harrowing nature of his stay, what scared Shocka most was being back home. He says that, as there was a lack of education around mental health where he grew up, people made judgments. ‘When we saw people speaking to themselves on the streets, we’d be told: “Stay away from that crazy person. They’re losing their mind”, with no acknowledgement of what their full story may be,’ says Shocka.

Whether he could recover was another concern; he vividly remembers going on Google to find evidence of a Black man who’d been sectioned and then went on to live a happy life. The search was unfruitful. ‘I didn’t think the cycle could be broken,’ says Shocka, who was most recently sectioned in 2022 after his mother died from cancer.

Part of the problem, he believes, is ‘no aftercare’. ‘Prisoners get more help, support and rehabilitation than people with mental health issues,’ claims Shocka.

He continues: ‘There’s a common theme amongst all the patients that you’re viewed as less than human, like the staff are just putting up with us in the weirdo section. It’s a feeling you get rather than anything in particular.’

The bigger picture

Kadra Abdinasir has worked in mental health policy for over a decade, and tells Metro that ‘Black people face some of the harshest inequalities in the mental health system, and tend to come into contact under coercion rather than intervention.’ The latest figures published by the NHS show that Black people are detained at four times the rate of white people.

This is even though they are more likely to need earlier support, as Black people experience structural inequities disproportionately that can contribute to poorer mental health outcomes, such as living in lower-income households, housing insecurity, and facing greater rates of unemployment, incarceration and school exclusions.

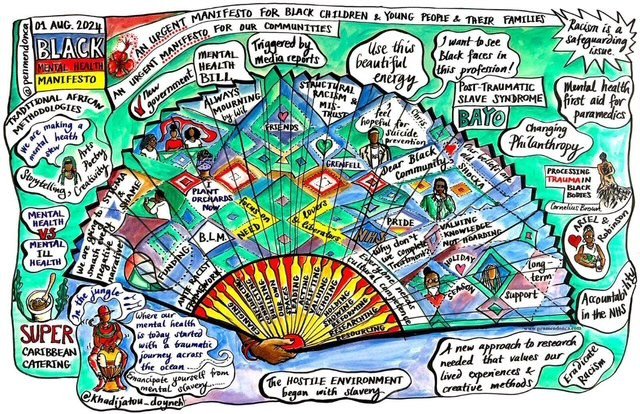

To combat the issue, Kadra is part of a team who’ve produced the Black Mental Health Manifesto. They aim to ‘break the cycle of a broken system which has continued to fail Black people when they are at their most vulnerable.’ Today, the document, originally published in spring 2024, is in parliament, presenting the key asks. This timing is important as a revived mental health bill is in its final stages, and they want to ensure it commits to tackling racial inequalities.

The Black Mental Health Manifesto

The Black Mental Health and Wellbeing Alliance, of which Mind is a supporter, is holding the parliamentary launch of its Black Mental Health Manifesto, which has six key asks:

- The government should develop and implement a comprehensive strategy to eradicate racism from society and appoint a cabinet-level minister to oversee this.

- The government must prioritise the reform of the Mental Health Act 1983.

- The government should put an end to ‘hostile environment’ policies, which harm or exacerbate mental health problems amongst refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in the UK.

- All NHS Trusts, VCSE (voluntary and community sector organisations) and mental health service providers should embed NHS England’s Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) by March 2025.

- The Department of Education should work with racialised communities to develop and embed an anti-racist and diverse curriculum that incorporates the histories and contributions of all racialised communities in the UK.

- Policymakers, academic institutions, and funders should actively invest in and engage with community research conducted by and for Black communities in a meaningful way.

For more information, you can visit here. The initiative is being supported by Black Minds Matter and Bayo.

Explaining why policies need to address Black mental health specifically, Shocka uses a childhood memory: ‘When we played football at school, whichever team was doing badly would get given good players to level it back out. That’s how humanity should be. Whoever is struggling should get the most help.’

‘If we get things right for the people that face the harshest inequalities in the mental health system, we get it right for everybody,’ Kadra adds, pointing out that early intervention is key. ‘Black children made up 36% of those in mental health hospitals, but just 5% of those in community services. We talk about the school-to-prison pipeline as a young Black man, but the school-to-mental health system is often hidden.

‘Why do their needs only come up at the crisis point?’ she asks. ‘Schools and community services should pick up earlier and talk to them, but instead, they are seen as badly behaved and given a response like school exclusion.’

Road to recovery

Kadra explains that ‘stigma’ around mental health also stops Black people coming forward. ‘They fear that getting a diagnosis might limit their job opportunities or lead to interventions from public bodies such as children’s services. Too often, Black communities face greater scrutiny and punitive responses instead of care and compassion,’ she says.

‘Racism is toxic to mental health, so they turn to the system, but then they are less likely to have positive recovery journeys. Sometimes the professionals have stigmatising attitudes towards Black communities, leading to discrimination.’ There is a notion that Black people are ‘strong and resilient’ so should get on with life’s traumas, which Kadra believes is entrenched within healthcare.

‘The services aren’t culturally competent. A lot of the workforce in the mental health space is white, middle-aged professionals, and they have a Eurocentric therapy approach, where you sit in front of somebody and talk, but some prefer integrating it into a creative activity or talking anonymously online,’ she explains.

Hopeful future

Shocka is open about his story because he wants to take the shame out of sectioning. He is doing this through various means, including a TEDx talk, his music releases, a YouTube series, A Section of Your Life, and a book of the same name, which features poems written during his last hospital stay.

‘If people want to know what it looks like to get sectioned multiple times, build yourself back up and have a good life, I want them to think of me,’ he says. ‘I show the possibility, but I want the next generation to take it to the next level. I hope there are more mental health advocates who are sectioned just once, and they learn amazing tools that I couldn’t figure out.’

Kadra adds: ‘The diversity of the UK needs to be reflected in decision-making and racism needs to be combated. We also want to see more investment in local organisations, which can build trusting relationships with communities, and more data on the issues, so we can get a clearer picture of what needs fixing.

‘If these things were instilled, there would be less disparity between white and Black people, feeling comfortable to talk about their mental health, and they would get the same quality of service.’

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing Josie.Copson@metro.co.uk

Share your views in the comments below.

Write Reviews

Leave a Comment

No Comments & Reviews