10 Feb, 2026 | Admin | No Comments

I told work I’d been sick – I was terrified they’d learn the truth

I was startled awake by my phone ringing in the middle of the night.

At first, my groggy brain mistook it for my alarm – but it was my mum.

‘It’s Luke,’ she said – and instantly, I knew something terrible had happened.

My younger brother was dead. He was just 24.

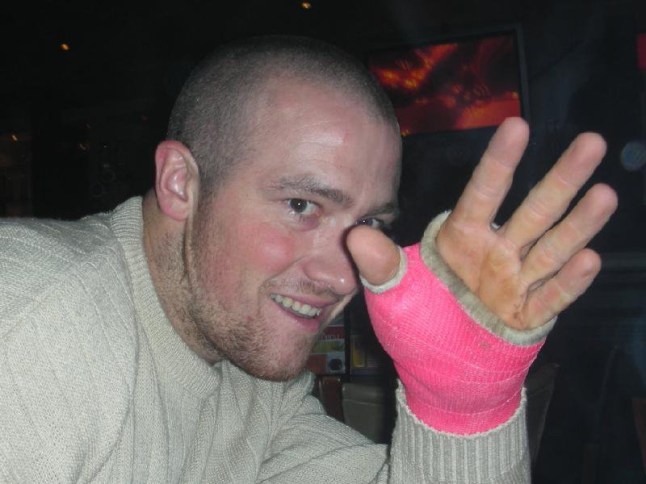

Luke had pulled over by the side of the road on the way home from work, and by the time the ambulance arrived it was already too late. He’d had cardiomyopathy: a type of heart muscle disease that made his heart swell and grow too large.

We never knew.

When I heard the news, the first feeling that rushed through my body was guilt. ‘I should have taken care of him’, I thought, telling myself we should have noticed how red-faced and short of breath he was.

The rest of that awful day in 2008 is a blur. I must have packed a bag and travelled home to my family, but I can barely remember.

What I do recall, though, is feeling unbearably nauseous, feverish and panicked.

That feeling stayed inside me as days turned into weeks. But I couldn’t explain all that pain and guilt and desperation to myself, let alone talk about it.

So I kept it all bottled inside, and didn’t even tell anyone at work what had happened. Instead, when I finally went back to the office after two weeks off, I pretended I’d been sick.

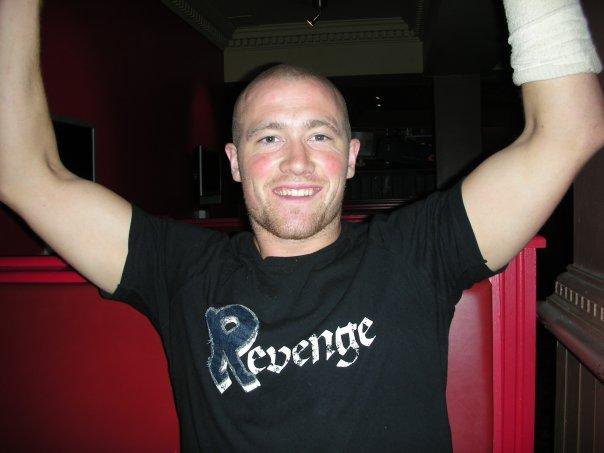

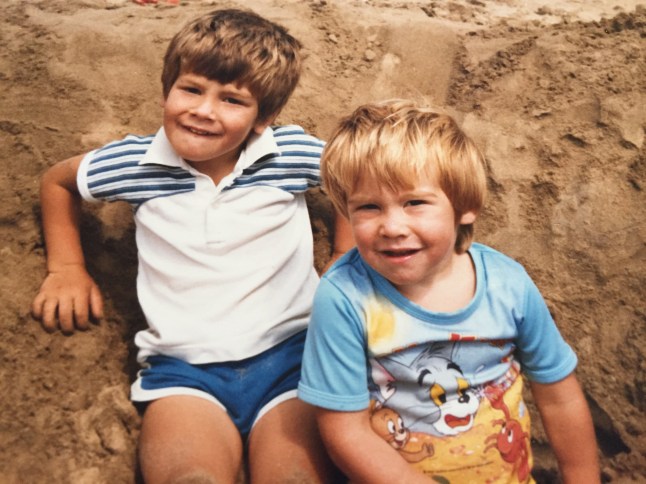

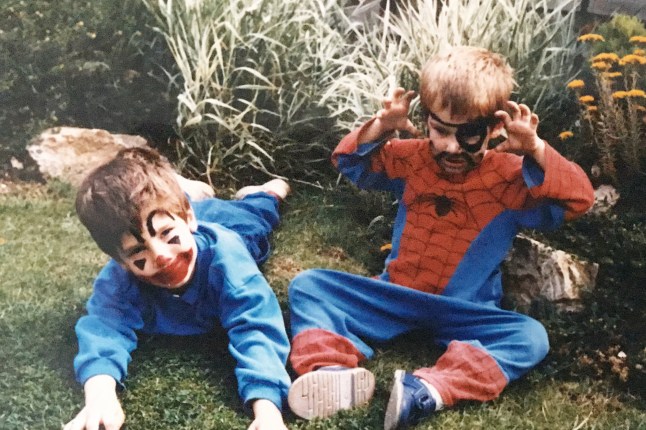

Luke was a whirlwind, and the world felt empty without him.

He was a pranker and a daredevil. He’d get in trouble at school because he couldn’t sit still: he was forever dreaming up some practical joke or elaborate scheme.

Life was always a rush for him, and I had to try my best to keep up – but I was his companion and co-conspirator, and we were often in fierce competition with one another.

Though I moved away from home as an adult, Luke stayed local, picking up jobs as a bouncer and then on a construction site. We would catch up whenever I came home, chatting and laughing about our shared history.

On the day he died, everything stopped making sense. The phone call from my mum kept replaying in my mind.

None of it seemed real. It was like a terrible dream that I couldn’t wake up from.

Without Luke around, I wasn’t sure who I was.

In the weeks after the funeral, lots of friends called, inviting me out or offering sympathy – but I kept making excuses. I didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t want help. I just wanted my brother back.

When I went back to work, I was ashamed and embarrassed of how broken I felt.

I would find myself feeling tearful and overwhelmed at my desk, and have to run to the loo to hide away and calm myself down. I swung between rage and sadness, anger and confusion.

I tried to push these feelings down, telling myself I was supposed to be stoic and strong for my family.

While my boss knew what had happened, no one else in the office was aware. I squirmed a little when I repeated the lie to my colleagues that I hadn’t been well, but I couldn’t bear the thought of being pitied at work.

I think some of my co-workers suspected there was more going on, but I became an expert at deflecting questions on how I was doing by giving vague answers and turning conversations back towards them.

I knew, if I spoke about my brother, I might start sobbing and never stop.

So I kept my head down, avoiding the break room and anywhere else I might get caught up in casual conversation – but I worried I was falling apart. I couldn’t sleep for longer than an hour or two at night, I was losing my appetite, I couldn’t focus at work.

That’s when I started writing.

At first I wrote short letters to Luke, telling him what he was missing and how angry I was that he’d gone and left us to pick up the pieces.

Wonder and Loss

Find out more about Sam’s book, Wonder and Loss, here.

Then I started writing journals in order to process what had happened, focusing on the moments I was at my lowest ebb – like the time I fleetingly thought I’d seen my brother again in the supermarket. I tried to write a little every evening.

By the time I changed jobs a year later, I felt able to try and be open about what I’d been through. I didn’t shoehorn my dead brother into conversation, but neither did I try to change the topic whenever bereavement came up.

But it was only through writing that I was able to articulate my grief to myself.

I wanted to keep Luke alive in spirit; and I got so much pleasure out of recording and reliving our shared history that I began to think it might be beneficial for others too.

That’s when I got the idea for my book, Wonder and Loss.

Writing the book meant facing the fear of being vulnerable. I had been so ashamed of my emotions that the only place I could be open about them was on the page, but now I was about to share them with the world.

This was terrifying; but seeing the book get published was incredibly worthwhile, because I knew others would know that they weren’t alone in their struggles with grief.

Nowadays, life is still sometimes messy and heartbreaking. Sometimes I feel good, and other days I hear one of Luke’s favourite songs in a movie or TV show and I’m plunged right back into heartbreak.

The difference is that now I know how to get a handle on these difficult times by setting my feelings down in words.

My advice for anyone going through a devastating loss is to be patient. We all grieve differently, and processing grief can be incredibly difficult.

Be kind to yourself, talk to others if you can – and maybe try putting pen to paper. Without writing, I would have lost myself completely in my pain; instead, I was able to map out a path through the darkness.

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing Ross.Mccafferty@metro.co.uk.

Share your views in the comments below.

Write Reviews

Leave a Comment

No Comments & Reviews